The Third Chapter of Lucknow’s Story – The Siege, the Silence, the Scars

The next day, I woke up early.

The elegance of Imambaras and the glow of chandeliers were still fresh in my mind. But Lucknow has another face. A quieter one. A wounded one.

If the first two days were about architectural renaissance, the third day was about resistance and ruin.

The Nawabi dynasty of Awadh, which began in the early 18th century, came to a tragic end in 1857.

To understand this, we must briefly turn the pages of history.

The East India Company arrived in India for trade. But in 1757, after defeating Siraj ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey, they began acquiring political power.

In Lucknow, power was shared between the Nawabs of Awadh and the British representatives. But tension was rising.

Then came 1857.

The Sepoy Mutiny — also known as the First War of Indian Independence — spread across North and Central India like wildfire. British houses were attacked near Lucknow. Officers and civilians from different regions took refuge inside the Lucknow Residency.

The Beginning of the Siege

The Residency was not a single building. It was a large complex of structures. Originally built around 1800 by Saadat Ali Khan II, it served as the residence of the British Resident and later the Chief Commissioner of Awadh.

On a rainy day in June 1857, refugees inside the Residency were listening to the gentle sound of raindrops.

Then came the first boom of cannon fire.

The siege had begun.

For nearly five months, the Residency faced relentless shelling and counter-shelling. By the end, the grand complex had turned into shattered ruins.

Most of us in India know this story. It is part of our textbooks. Part of our national memory.

But reading about it and walking through it are two very different experiences.

Exploring the Residency Complex

I recommend visiting the Residency early in the morning. Later in the day, the lawns turn into casual hangout spots. Morning gives you silence. And silence is important here.

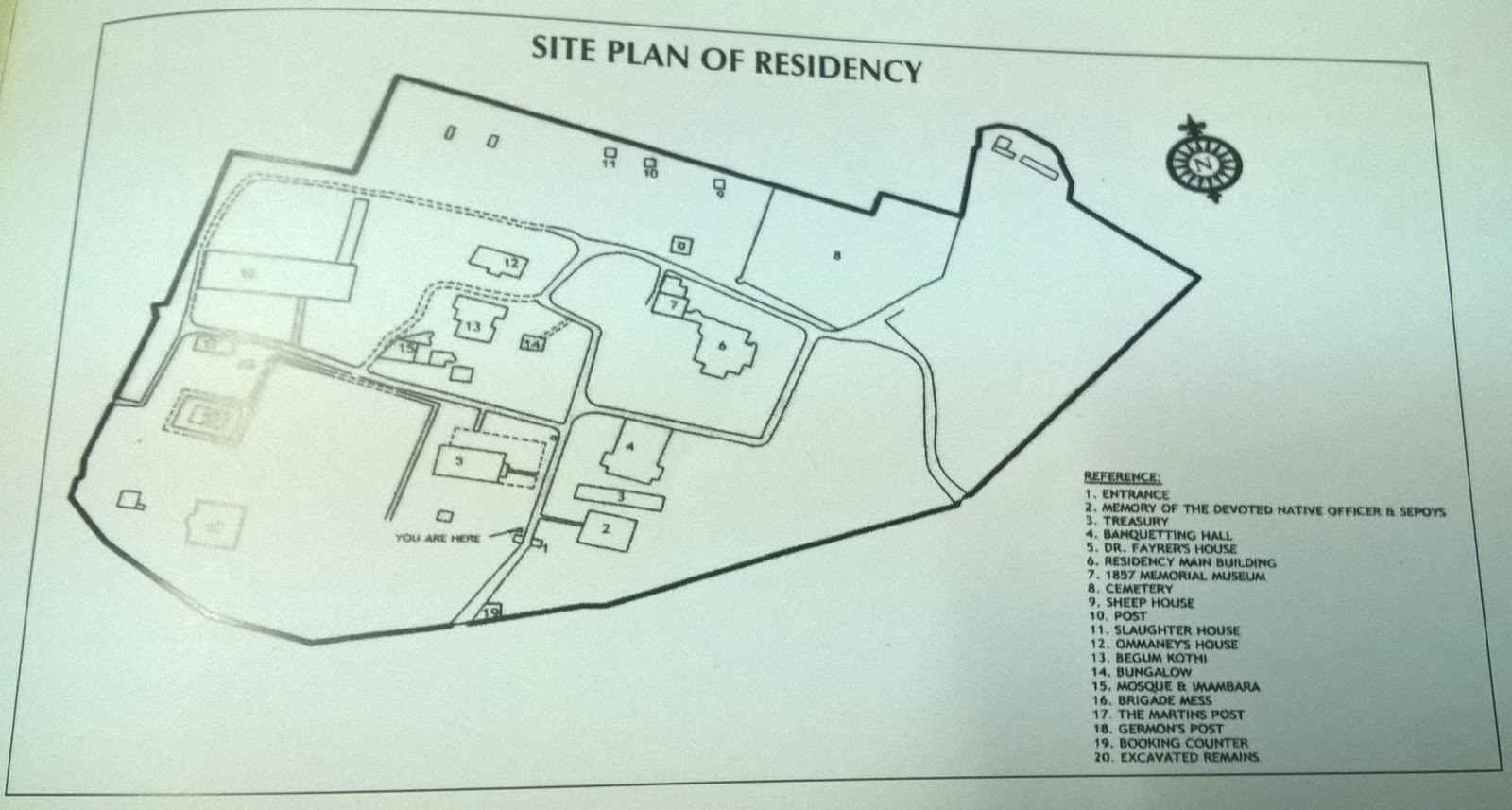

As you enter, look at the map carefully. Hiring a guide helps, but even without one, the ruins speak loudly.

The first structure you see is a memorial pillar dedicated to the native officers and sepoys.

Next comes the Treasury House. It is a double-storied building with Rajput and Awadhi arches. During the siege, it was converted into an ordnance factory to manufacture Enfield cartridges.

Beside it stands the Banquet Hall, once built as a Daavat Khana by Saadat Ali Khan II for British Residents and distinguished guests. It was once the most imposing structure in the complex. Today, it stands broken, scarred by cannon fire.

I paused there for a while. You can still see the marks of shells on the walls.

Lives Inside the Siege

There was a doctor here — Dr. Fayrer. His house had a flat roof and low ceilings. It also had a tehkhana, an underground chamber, where pregnant women were sheltered during the bombardment.

Walking further along the main road leads you to the Residency Main Building.

Built at one of the highest points in Lucknow — second only to the minarets of the Asafi Mosque — it once offered a commanding view of the city and the Gomti River.

During the siege, the eastern entrance was barricaded with furniture and books.

Today, the building stands like a skeleton. The walls are pierced with cannon marks. The structure feels frozen in time.

Adjacent to it is a museum. I chose to walk first.

Cemetery, Ommaney’s House and Begum Kothi

Further down the road, you reach a bifurcation. To the east lies the cemetery. Nearby stand the Sheep House, Post, and Slaughter House.

On returning to the main road, you see Ommaney’s House on the left. Mr. Ommaney, a judicial commissioner, was killed here in July 1857 by a cannon shot.

Then comes Begum Kothi.

Probably the oldest structure in the Residency complex, it was originally built by Asaf-ud-Daula. Over time, ownership changed multiple times. Eventually, it became associated with Vilayati Begum, the British wife of Nawab Nasir-ud-Din Haider.

Unlike other Residency buildings, Begum Kothi reflects traditional Lucknow architecture.

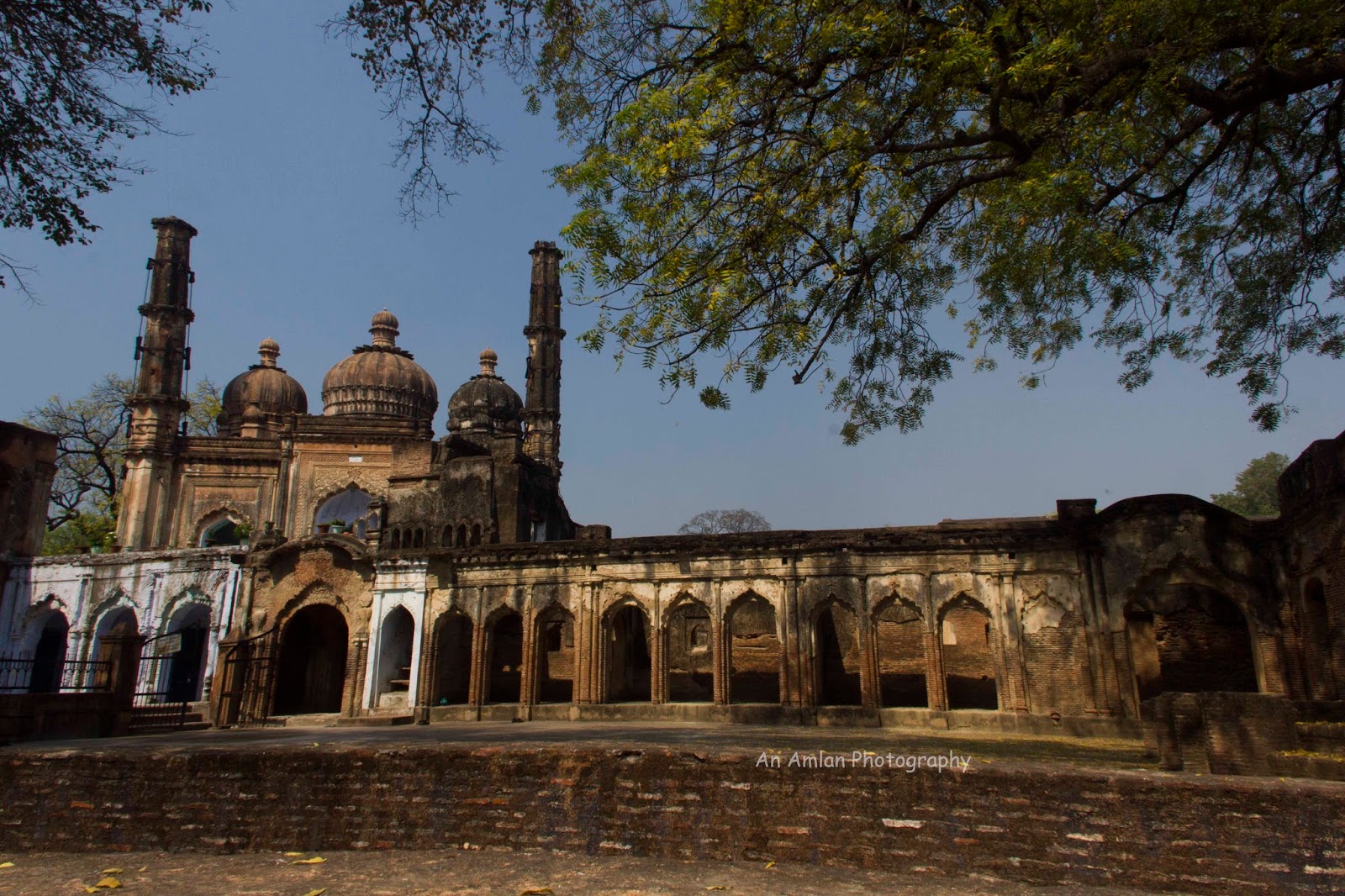

Nearby stands a mosque and an Imambara built later. The Imambara is now roofless. The mosque, though damaged, still shows fine stucco artwork.

Further ahead are the ruins of Brigade Mess, Martin’s Post, and Germon’s Post.

When Ruins Speak

On my way back, I saw the War Museum. I did not enter.

The walls had already told me everything.

Fresh cannon marks still scar the bricks. Standing there, I could almost hear the sound of gunfire. The cries. The confusion. The fear.

A magnificent architectural complex was reduced to rubble in months.

Lucknow is not just about elegance and Awadhi refinement. It is also about endurance.

If Bara Imambara tells the story of creation, the Residency tells the story of destruction.

And yet, both are part of the same city.

As I left the Residency complex, the morning sun was rising higher. The ruins stood silent behind me.

History had spoken.

And Lucknow, once again, had whispered another story.

You can also check the first two parts :

Lucknow Tour: Part 1 – Asafi Imambara (Bara Imambara) and Rumi Darwaza

Bibliography:

- Monuments of Lucknow by R S Fonia (published by Archaeological Survey of India)

- Site plan courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India

[…] And the story of Lucknow was not over yet. Next part: Lucknow Tour: Part 3 – Residency: The silent witness of Sepoy Mutiny […]

LikeLike

[…] my previous posts, I shared the detailed stories of Bara Imambara, Chhota Imambara, and the Residency. This two-day Lucknow itinerary is a simple guide. No deep architectural explanation here. Just […]

LikeLike