There are cities you visit. And then there are cities that whisper to you.

Lucknow is one of the oldest living cities of India. Its story stretches so far back that even the epic Ramayana remembers it. In those distant days, the city was known as Laxmanabati, named after Lakshman, the devoted brother of Lord Rama.

Yet history was not always kind to Lucknow.

While Delhi and Agra rose proudly on the banks of the Yamuna, glowing with imperial splendor, Lucknow stood quietly beside the river Gomti. The Yamuna would eventually merge into the mighty Ganges and boast of her glorious cities. The Gomti too flows into the Ganges, but her story was softer, less celebrated.

Sometimes I imagine the three rivers meeting at dusk. Yamuna speaking proudly of Delhi and Agra. Gomti listening silently, hiding her tears like a shy girl among confident companions. Perhaps destiny heard that silence. Perhaps God decided that Gomti too deserved a grand story.

And so began the golden chapter of Lucknow.

When Empires Fall, Cities Rise

In 1707, after the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughal Empire began to weaken. The earlier Mughal rulers — Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan — had built an empire of art, culture, and relative harmony. But Aurangzeb’s rule was marked by religious rigidity and political strain. After him, the successors were unable to hold the empire together.

When central power weakens, regional powers rise.

In western India, the Marathas under Shivaji were asserting their strength. In the north, a new power quietly prepared its ascent — the Nawabs of Awadh.

Until then, the Nawabs were Subedars under the Mughals. But in 1722, Burhan-ul-Mulk Saadat Khan laid the foundation of an independent Awadh. The first capital was Faizabad. And then came a man who would change the destiny of Lucknow forever.

His name was Asaf-ud-Daula.

The King Who Dreamed in Brick and Mortar

In 1775, Asaf-ud-Daula shifted his capital from Faizabad to Lucknow. That decision changed everything.

He was not just a ruler. He was a visionary. He understood something very powerful — power alone does not make a city immortal. Art does. Architecture does.

Under his patronage, Lucknow transformed. Gardens bloomed. Palaces rose. Arches curved against the sky. The Gomti finally had something to tell Yamuna.

People often call Asaf-ud-Daula the true architect of Lucknow. And when you stand before the great monuments he built, you understand why.

The most iconic among them is the magnificent Bara Imambara, also known as Asafi Imambara.

Come, let me take you there.

Entering the Bara Imambara

I still remember the first time I stood before the gate of the Bara Imambara complex. The ticket in my hand felt like an entry pass to another century.

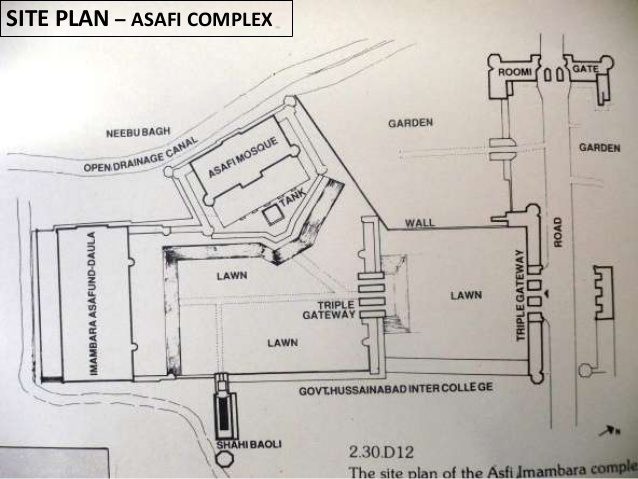

With the same ticket, you can explore:

- Bara Imambara (Asafi Imambara)

- Rumi Darwaza

- Chota Imambara

- Hussainabad Picture Gallery

- Hussainabad Clock Tower

- Hussainabad Talao

But I chose to begin where history feels heaviest — the Bara Imambara itself.

Outside, I hired a tonga. The slow rhythm of horse hooves against the road felt poetic. I asked the tonga driver to wait. He smiled knowingly. “You will take time,” he said. He was right.will take you to Bara Imambara. Please don’t leave the tonga puller as he will take you to Chhota Imambara.

The Story Behind the Structure

As I crossed the first gateway and walked toward the second, I thought of how this masterpiece came into existence.

Asaf-ud-Daula wanted the finest architect. He invited talent from far and wide. After a competitive process, he chose a Delhi architect named Kifayat Ullah.

The project required vast land. A ruler could easily displace residents. But Asaf-ud-Daula was known as a people’s king. He chose a site near the Gomti. Even there, a small hut stood in the chosen land. It belonged to an elderly woman named Lado.

She refused to leave at first. Instead of using force, the Nawab met her personally. He explained his vision. Moved by his humility, she agreed — but with a condition. Her hut must be respected. That story stayed with me. True greatness lies not in power, but in empathy.

Inside the Giant

When you enter the main courtyard, the grandeur unfolds slowly.

The Imambara stands before you. On the left is Shahi Baoli. On the right rises the majestic Asafi Mosque.

I followed a simple rule — visit the Imambara first, while energy is high.

At the entrance, you remove your shoes. Keep your socks on. Later, on the terrace, the heated floor will remind you why.

I hired a guide named Mohammed. If you truly want to understand this monument, take a guide. Stories live in their voices.

The Hall Without Beams

The central hall is breathtaking.

It measures roughly 50 meters in length, 16 meters in width, and about 15 meters in height. And here is the wonder — there are no beams supporting the ceiling.

The vaulted chamber houses the tombs of Asaf-ud-Daula and his architect Kifayat Ullah. Builder and dreamer resting side by side. Around the hall are eight chambers built at varying heights. Above them lies the legendary Bhulbhulaiya — the labyrinth.

Getting Lost on Purpose

The Bhulbhulaiya has 489 identical doorways.

It was designed strategically. Some staircases end abruptly. Some lead to sudden drops. Some bring you back to where you started. Only a few lead out.

There are legends that hidden tunnels connect it to the Gomti, to Faizabad, even to Delhi. Strategically, it makes sense. Escape routes were essential in uncertain times.

The acoustics are astonishing. A whisper in one corner can be heard in another. A struck match echoes faintly across the chamber.

But beyond technical brilliance, the real joy is simple — getting lost.

I tried deliberately. I climbed stair after stair. Took left turns and right turns. After several attempts, I found myself exactly where I began.

Mohammed laughed gently and guided me out.

From the terrace, the city of Lucknow spread before me. Old domes. Narrow lanes. Modern rooftops blending with history. I stood there for a long time. Some places you visit. Some places you absorb. When I came down, I tipped Mohammed extra. Not just for information. For storytelling.

The Asafi Mosque

Next, I walked toward the Asafi Mosque.

It is the largest mosque in Lucknow, positioned thoughtfully so that anyone within the complex can offer prayers.

A flight of steps leads upward. But entry is restricted to Shia Muslims. I have visited Jama Masjid in Delhi, Nakhoda Masjid in Kolkata, and Sixty Dome Mosque in Bangladesh without restriction. But here, I could only admire from outside.

The mosque is built with Lakhori bricks and decorated with stucco patterns — floral motifs, geometric designs, arabesque forms. Interestingly, you can detect subtle influences from Hindu and Buddhist architecture.

That fusion is what defines Indo-Islamic architecture — a dialogue, not a conflict. From the early days of Qutb Minar to the grandeur of Lucknow, the style evolved beautifully.

Shahi Baoli: The Royal Well

Opposite the mosque lies the Shahi Baoli.

India’s summers are unforgiving. Water storage was essential. Baolis — stepwells — were engineering solutions to climate challenges.

This baoli was built in seven levels. Four remain below water, three above. The lower section includes a four-storied octagonal block.

Mohammed showed me something fascinating. From certain vantage points, you can see the reflection of anyone entering the baoli in the water before they see you. It was a surveillance mechanism.

When I visited, the well was dry. Perhaps climate change has altered the water levels. Still, the structure speaks of technical brilliance and aesthetic balance.

Rumi Darwaza: The Gateway of Grace

After finishing the complex, I returned to my waiting tonga and rode toward the Rumi Darwaza.

Standing about 100 meters from Bara Imambara on the old Hardoi Road, this grand gateway once marked the ceremonial entrance to the city.

From one side, it resembles a massive mihrab framed by layered arches. Lotus panels and geometric patterns decorate its surface.

From the other side, it feels different — almost Rajput in influence, with multi-foiled arches and floral carvings.

At the top sits a pentagonal structure. Minarets hint at Mughal inspiration.

Every level changes subtly in design. It is not just a gate. It is a statement.

When I stood beneath it and looked up, the sky framed its arch perfectly. I felt small. But in a beautiful way.

Lucknow’s Renaissance

Asaf-ud-Daula and Kifayat Ullah did more than construct buildings. They reshaped identity.

They respected ancient Indian traditions while embracing Islamic aesthetics. They blended styles without erasing roots. They gave Indo-Islamic architecture a refined expression.

Lucknow experienced a renaissance.

And as I walked back through its lanes, past kebab stalls and old havelis, I felt something deeper than admiration. I felt gratitude.

Because cities like Lucknow remind us that decline is not the end. Sometimes, it is the beginning of transformation.

The Gomti found her voice.

Second part of the day is mentioned here: Lucknow Tour: Part 2 – Hussainabad Imambara (Chhota Imambara), Clock Tower, Picture Gallery and Hussainabad Tank

Reference:

- Monuments of Lucknow by R S Fonia (published by Archaeological Survey of India)

I don’t ordinarily comment but I gotta state thanks for the post on this great one : D.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] my previous post, I spoke about the architectural rebirth of Lucknow under Asaf-ud-Daula and the grand…. That was the beginning of Lucknow’s […]

LikeLike

[…] Lucknow Tour: Part 1 – Asafi Imambara (Bara Imambara) and Rumi Darwaza […]

LikeLike

[…] my previous posts, I shared the detailed stories of Bara Imambara, Chhota Imambara, and the Residency. This two-day Lucknow itinerary is a simple guide. No deep […]

LikeLike